Social Reforms of America: Early to Mid 19th Century

Correctional Institutions

As people began to realize institutions for misdemeanants should be correctional rather than penal, they recognize that these people, mainly children, are arrested for misconducts resulted from poverty or lack of adequate training. By confining them with the hardened criminals, they are deprived the oppurtunity of becoming educated to live better lives. Moreover, merely discharging them can only bring them back with more serious charges. Many local charity or religious dominations try to solve the situation by increasing the number of orphan asylums. However, the problem presents not only to the few of the unfortunate children in the cities, but also children who are in poverty living in both urban and rural areeas. With little chance of encouragement and support, these children fell into the careers of crime. They were not convicted by judges due to lack of provision for these juvenile offenders. The vicious cycle continues.

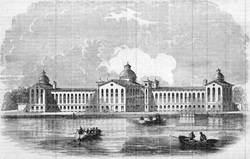

Agnizing the deep roots of this illness in society, Professor John Griscom along with his new charity group probuilt the New York House of Refuge

New York House of Refuge

in 1825. The new refuge provided junvenile delinquents a place for shelter and warmth. Soon other states, such as Philadelphia and Massachusetts, followed this example and built similar reform schools. These reform schools taught elementary subjects and offered children mechanical training--shoemaking, weaving, carpentry. The young inmates were taught "the habits of industry and the principles of religion," wrote Thomas Hamilton. They rose at sunrise and went to morning prayers; they attended school from five-thirty to seven, then had breakfast and worked until noon. After lunch they worked for another four hours until supper. Afterwards, they would work on school work for another hour or two before evening prayers. The children were allowed to interact freely during the day, but were confined in separate cells at night. When a child showed evidence of reform and acquired skills of trade, he would be apprenticed to a farmer or artisan. Girls, on the other hand, were placed as household servants.

Following the early American colonialists' practices of well-ordered, Reverend E.M.P. Wells, the superintendent of house of refuge in Boston,

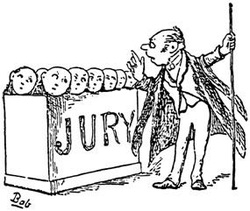

decided to work out a system of self-government. It is a system where children were allowed to participate by the consent of a majority if inmates. The ones who behave properly were given the right to vote, hold office, and to elect his own magistrates and monitors. If their conduct was not satisfying, twelve jurors would be selected from among the boys themselves. Each case was tried as in a real court to keep justice. From this exercise, the children learned not to denounce each other's faults and no corporal punishment was inflicted as long as they confess sincerely. Separatation of misdemeanants and criminals have proven to be fruitful, for almost fifty-five percent of the boys in the New York school worked genuinely as apprentices.

Nevertheless, in the pre-Civil War period, reformers devoted most of their attention to prisons and penitentiaries. It wasn't until later in the nineteenth century that the reform schools were widely adopted.

Nevertheless, in the pre-Civil War period, reformers devoted most of their attention to prisons and penitentiaries. It wasn't until later in the nineteenth century that the reform schools were widely adopted.